Can Bengal’s vanishing childhood games be saved? – GetBengal story

"I

t was 1955–56. My childhood days. Girls would play hopscotch on the rooftop, and a few of us boys played ‘cops and robbers’ (Chor-Police). That game had a strange kind of thrill. Gunfire was raging across the world and we used to chant a rhyme—“Saregamapadhani / Bom phelechhe Japani / Bomer bhetor keuṭe shap / British bole bap re bap” (Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni / A bomb was dropped by the Japanese / Inside the bomb a deadly snake / Even the British cried out for heaven’s sake).These rhymes still carried the echoes of the war years. Do these games still exist? Perhaps, in some corners. But games lose their fun without spectators. The noisy laughter of children within families seems to be vanishing.” — Author Swapnamoy Chakraborty recalling his childhood.

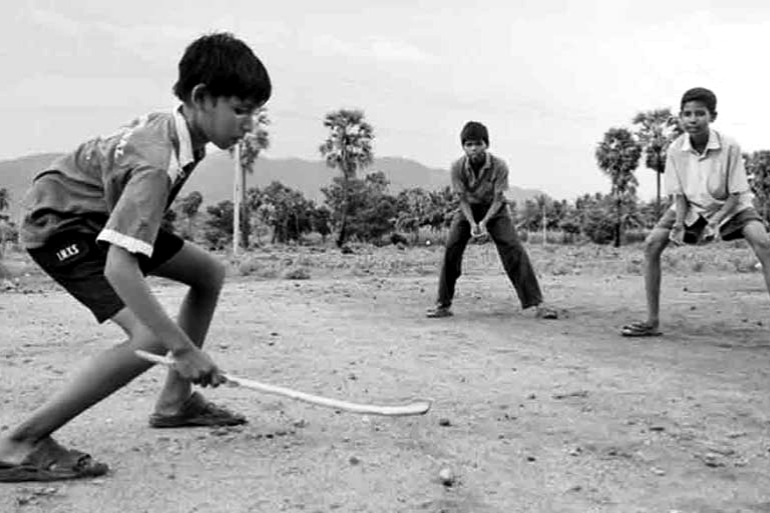

Games—whether it meant sitting quietly in absent-minded wonder or running wildly from one corner to another, remain etched in memory long after the days are gone. Childhood games live in the heart. In this busy, complicated life, each of us secretly longs to return to those riverbanks of childhood. Sometimes it was football played with a pomelo, cricket improvised with a wooden plank as bat, a coconut stalk as ball, and a makeshift wicket from bricks or bamboo. Those were the stolen moments—afternoons fading into dusk, the call of old friends, scraped knees, bruised elbows, mothers scolding when we returned late, only to sit sulking with books once evening lamps were lit. It was a beautiful life. Perhaps it still is. But among the memories we cling to most dearly are the games. Which ones? Tag, hide-and-seek, “eeny-meeny-miny-moe,” blind man’s buff, cops and robbers, “king-thief-minister-soldier,” “buṛi basanti,” hopscotch, “red light–green light,” marbles, “kumir-danga” (crocodile-land), “danguli,” and countless others.

Blind Man’s Buff (Kanamachi)

In this game, a piece of cloth was tied around one child’s eyes—he became the “blind one.” Others circled around like buzzing flies, chanting “Kanamachi bho bho” while tapping him on the shoulder. The blindfolded child would try to catch someone. If he managed to catch and correctly identify the person, that child would then take the role of the “blind one.” Even today, in many rural places of Bengal, children still play it.

Tag (Dhara-dhari)

One of the most popular childhood games is tag—chasing and touching, one trying to catch the other. Its popularity is universal. Not just in Bengal but as far as Britain. In fact, it has even entered the arena of World Cup–style competitions. Adults play it too. In Bengal we call it dhara-dhari or choyaa-chhui, in Britain it is known as Chase Tag. Athlete Enis Maslich once said, “It is like hide-and-seek with professional athletes. The speed makes it insanely thrilling.”

Hide-and-Seek (Tuki–Dhappa)

A 19th-century painting by artist Friedrich Eduard Meyerheim shows three children playing hide-and-seek in a forest. The painting became immensely popular, and so did the game. One child covers his eyes, counts to a number, while the others hide. Then comes the shout: “Ready or not, here I come!” In Bengal, the seeker might shout “Tuki,” and when someone is found, others would yell “Dhappa!” The game spread across the world under different names. In his 1931 ghost story collection, writer A. M. Burrage even referred to it as “Smee.”

Cops and Robbers (Chor-Police)

Singer Shivaji Chattopadhyay remembers playing pittoo in his Shyambazar neighbourhood: “We would stack shards of tiles in a tower, then hit it with a rubber ball. The challenge was to rebuild it before the other team struck us out with the ball. Those fields are gone now, as are many of those games. But I still play blind man’s buff at home with the kids. I also played hopscotch as a boy, back then, there was not much distinction between boys’ and girls’ games.”

Nearly 150 years ago, children across the subcontinent were already playing chor-police. There was no limit to the number of players. Children split into two teams, one became the police, the other the thieves. The police chased the thieves to mark them out. Simple, endless fun.

In Bengal, the rules and names of these games often change from place to place. Football, cricket, tennis, badminton, chess and their rules are the same everywhere in the world. But these folk games shift and evolve, earning the label “local games.” They remain rural, free-spirited, unpretentious joys. Not just for children—even adults joined in, role-playing as kings, thieves, cooks, servants. Sometimes hopscotch and “jhal jhapṭa,” sometimes crocodile-land (Kumir- Danga) and “danguli.”

Actress Sohini Sengupta, recalling her childhood in Allahabad, said: “I did not have many friends, so I played alone—pretend cooking, pretend teaching. I used to scold imaginary students and whack them with a scale. Now when I actually teach, I make the best teacher! I enjoy nostalgia but don’t like clinging to it. Childhood has changed. Today’s children play video games—and that does not upset me. People should do what makes them happy. I am a Sudoku addict myself.”

Until the 1990s, entire generations grew up on these games. Then slowly, modernity and its machines took over. We learned to chase after busyness, glued ourselves to remotes and cell phones. Swapnamoy Chakraborty reflects: “Now, there is no such environment, no playmates. Rural Bengal still has open fields, but even there politics seeps in, dividing children along family lines. A child thinks—‘My father fights with his father, so I can’t play with him.’ These things shape a child’s psychology, though few care to notice. In our time, such divisions didn’t matter. Brahmin or Bagdi, Hindu or Muslim—we all played together. At my Hare School I had many Muslim friends. Today, even in children’s rhymes, politics creeps in. Around 2006–07, I heard kids chanting: ‘Chorai pakhi barota, dim pereche terota / ekṭa dim kosto, BJP’r kosto.’ Even innocence has become politicized.”

And yet, if you listen closely in Bengal’s villages, you will still hear the chorus of “Tuki!” and “Dhappa!” The hum of Kanamachi bho bho still echoes in playgrounds. Some children still keep the folk games alive.

Poet Sukumar Ray once wrote in his verse Ajab Khela: “Abar anke abar moche diner pare din Apon sathe apon khela chole biramhin. Foray na ki sonar khela? ronger nahi par? Keu ki jane kahar sathe emon khela tar? Sei khela, je dharar buke alor gane gane Uthchhe jege – sei katha ki Surjo mama jane?” (Again and again it draws, again it erases,/A game with itself, endless through days./Whose game is this, of colours untamed?/Does even the sun know the name?) Games with oneself will always go on. But surely the sun understands our grief. And when the evening bell rings, he will whisper—“Come, let’s play again.”

(This article on the vanishing childhood games of Bengal was written for Bongodorshon. Suman Sadhu spoke on behalf of Bongodorshon with writer Swapnamoy Chakraborty, singer Shivaji Chattopadhyay, and actress Sohini Sengupta.)

Note : Translated by Debamita Ghosh Sarkar To read the original Bengali article, please click: https://www.bongodorshon.com/home/story_detail/lukochuri-kanamachhi-danguli-ekkadokka-the-games-that-still-call-back-in-busy-times